IJS Acquires Luckey Roberts Collection

Newark

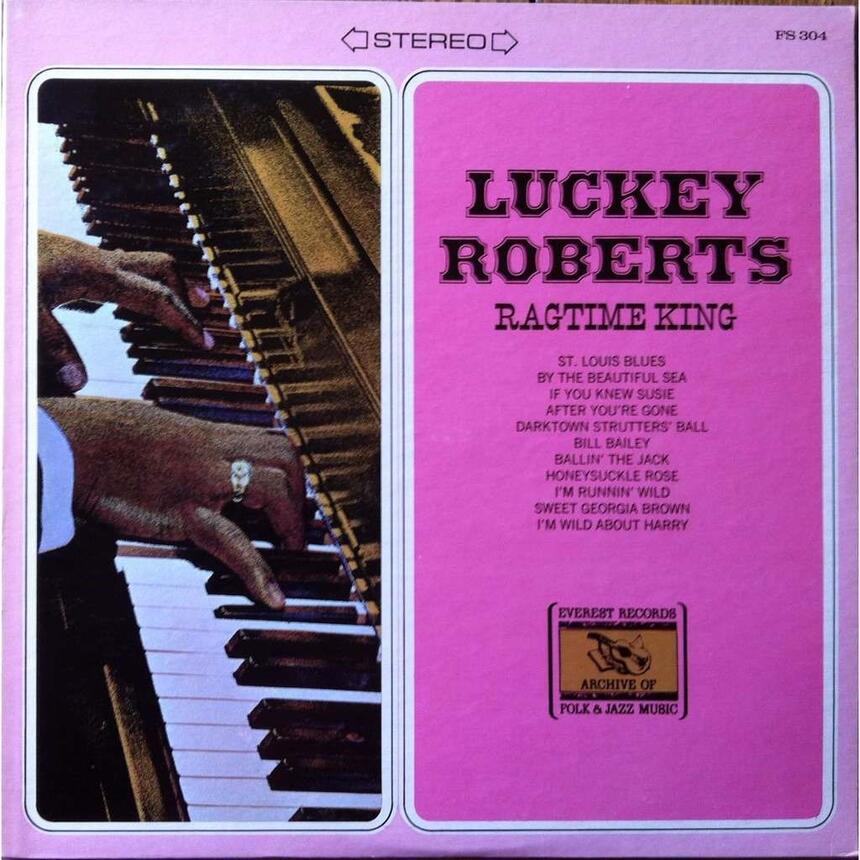

The Institute of Jazz Studies recently acquired the collection of stride pianist and composer Charles Luckeyth Roberts, better known as Luckey Roberts (1887-1968). Roberts was an influential composer and considered the most technically gifted member of the post-ragtime stride school.

Besides Roberts’s papers, the collection also contains those of Lena Sanford, a professionally trained operatic singer who Roberts would eventually be married to for over 40 years. Her career has received less attention than Roberts's. The collection includes correspondence, photographs (many inscribed), music (manuscript and printed), scripts, production notes, unique audio recordings, music publishing records, scrapbook, clippings, ephemera, contracts, one of Sanford’s dresses, and stock certificates, along with detailed documentation of provenance and a related collection of audio interviews. The collection also features never-before-issued recording of Roberts, an open reel tape with pianist/composer Eubie Blake, and several instantaneous discs. This is a unique early jazz collection, with rich, comprehensive documentation of Luckey Roberts’ career as a pianist, composer, director, bandleader, recording artist, publisher, and club/business owner. Roberts, a Philadelphia native, was an A-list entertainer, an influential, pioneering, and prodigiously productive figure in black musical theater, vaudeville, music publishing, and early Harlem stride-style piano who started in the industry as a child performer. He had close relationships with major figures such as James Reese Europe, George Gershwin, Will Marion Cook, Vernon and Irene Castle, Alex Rogers, Bunny Berrigan, Eubie Blake, Noble Sissle, James P. Johnson, Duke Ellington, Rudi Blesh, Benny Goodman, and Willie “The Lion” Smith, to name a few. Roberts’ renown as a talented rent party pianist led to lucrative private engagements and a reputation for composing piano music beyond the ability of even the top stride performers. A successful businessman, Roberts’ professional accomplishments are remarkable given the discrimination and exploitation faced by black entertainers in the early 20th century, and few extant collections from this time period exist that offer the range or depth of documentation of this era in black music history.

The collection has never been publicly accessible and has been carefully protected by Roberts’s family and descendants and lovingly cared for, especially by the donor of the collection, Roberts’s great-granddaughter, who took over her aunt’s role as collection steward around 2016. The Institute now has the opportunity to provide the first public access to these materials, which will be of interest to a wide range of institute patrons across disciplines. The collection will be processed and made available to researchers in the near future.

Recent News

- Open and Affordable Textbooks Program Eases Financial Burden for Rutgers Students

- Rutgers University Libraries Selected by the Association of Research Libraries to Participate in Inaugural Strategies Institute

- During Rutgers Giving Days, Support Students Across Rutgers University Libraries

For the Media

For questions about this story, please contact: